I am talking to Phyllis Young at Oceti Sakowin about the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and her thoughts on clean renewable energy. The day is hot and sunny. A dry wind blows through the camp creating dust devils as horses parade down the main dirt road lined with flags of sixty first nations. We are seated in the shade of a food tent. Children laugh and play around us and the kitchen fire throws smoke our way. I can see white clouds in the reflection of her slightly mirrored glasses as they float over the camp in a timeless sky. The Standing Rock action has grown from 500 when I arrived to now over 5000 water protectors.

I am an old white man. Conspicuous in my race when I first arrived, I feel both welcomed, though sometimes choose to feel slightly uncomfortable here. Perhaps it is my white guilt.

Coming here is not a Dances with Wolves experience for me. It is about the earth killing climate pollution of DAPL. To me the local injustice and the time-delay injustice of climate change are the same. We use up the earth and our air just as we use up and discard marginalized people. To me, distance from the earth is a form of diminishment, as is distance from one another.

My self-sourced discomfort is partly from the understandable caution that many native Americans take at this action. “Who are you, where do you come from, and why are you here?” are questions that are often asked. The pipeline companies are running disinformation campaigns and may also be placing people to infiltrate. I answer as best I can. I am here for my grandkids.

I am humbled by Young’s generosity in taking time to talk with me. It is a characteristic I find in many who have a quiet strength. It is humility and respect for others. It is an attitude of openness and reflection. She has answered many questions today, and listens to mine patiently.

Halfway through our conversation, we are interrupted by an announcement over the camp loudspeaker. It is another white man. His name is Soderman, a descendent of General William Harney for whom Harney Peak in South Dakota is named. It is the highest peak in the Black Hills or the sacred area called the Paha Sapa by the Lakota.

General Harney led troops in the Battle of Ash Hollow, also known as the Harney Massacre where 86 Brulé Lakota were killed, half of them women and children. This was in retaliation for the Gratten Fight by the Sioux where they killed 29 soldiers after one of the soldiers assassinated their chief, Conquering Bear.

Soderman has been working with others and native groups for years to convince the U.S. Board on Geographic Names to rename Harney Peak. He apologizes for the actions of his ancestor. But now he has news. The Governor has given final approval to change the name to Black Elk Peak* after the famous Lakota medicine man. A spontaneous ululation from dozens of women rings across the area. I look over at Young and she removes her glasses to wipe away a tear.

In this simple reflection, I am moved as well. In my white privilege I understand this name change as a small thing, but then have this perspective shattered by seeing it have such a big impact. I have never had my history erased, or my lands taken, and my people wiped out. Nothing atones for this, but small things may help others.

That night I am sitting around a small fire with Clint Cayou, an Omaha-Ponca from Colorado. I tell him about my grandfather who was a blue coat. From letters, I know he was with Kit Carson at Council Bluffs when five great Sioux nations gathered for treaty talks. Despite Carson’s sympathetic portrayals, his actions showed him to be brutal towards native Americans in a number of campaigns. My grandfather had advised attacking the gathering, but was chastened by Carson at the time, and a treaty was eventually signed. Though we know now what happens to treaties.

That night I am sitting around a small fire with Clint Cayou, an Omaha-Ponca from Colorado. I tell him about my grandfather who was a blue coat. From letters, I know he was with Kit Carson at Council Bluffs when five great Sioux nations gathered for treaty talks. Despite Carson’s sympathetic portrayals, his actions showed him to be brutal towards native Americans in a number of campaigns. My grandfather had advised attacking the gathering, but was chastened by Carson at the time, and a treaty was eventually signed. Though we know now what happens to treaties.

I never met the man who was my grandfather, but they say the sins of the father are visited upon the sons. Once I know these facts, it is hard for me to deny or justify them. I am also culpable. It occurs to me that this is not about me alone. It is only about me in the sense that I can work to change the injustice. But it is also about white systemic racism and genocide.

I talk with Clint about Soderman and my grandfather. I am unsure what amends I can make? Clint is quiet, as is his habit. He doesn’t pretend to offer advice, but he finally says, “Just do what your heart tells you.” This seems an essential truth.

If we are honest with ourselves, we can be honest with others, and perhaps history. I apologize to Clint for my grandfather actions, and then for my own obliviousness, though this is no excuse. I will find ways to make amends, and in the coming months, I do.

I think about Clint’s advice when I see the George Floyd video. How have we come to this point where we are so distanced from each other that we can hate and kill each other? Is this really what we want in our hearts? Are we so fearful and insecure?

Fear keeps us apart. Fear keeps us from acknowledging and seeing others. It keeps us from even making small gestures like renaming peaks. I wonder then if we can’t see others, how can we help each other? Some say we need hope.

To my way of thinking, the antidote to fear is not hope, it is courage. The courage to see and respect others for who they are, just as we’d like to be seen and respected for who we are. Sometimes this is small courage such as simply saying hello, or giving an interview. Sometimes it is an apology. Other times is requires big courage such as putting your body on the line. Courage requires action. Otherwise it is only words.

But what are the actions? Individually, we each need to find our own and there are thousands. But together, taking down monuments is one. So is renaming a peak in the Paha Sapa. It is letting go of the fear and hate, and building trust and respect. It is based on finding a mutual truth. And it is finding that we are not diminished by acts of reconciliation or kindness. We are strengthened.

Of course other actions are required for justice, so reconciliation is not complete in itself. But it is a place to start.

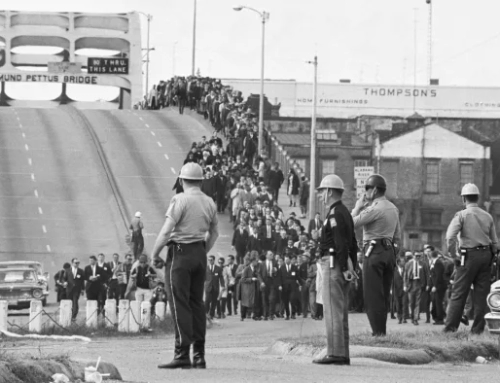

Reconciliation is one of those actions that people want to avoid because it is scary and seems to require big courage. It begins with small individual actions and builds to collective action. But here’s the deal, the courage it requires is contagious. It attracts and dissipates fear. When one person kneels on the field, stands against a tank in Tiananmen square, or says no to a pipeline on their lands, it makes it easier for others to join them. It makes justice and a better world possible.

Hobie,

‘We are all connected. Savor the Earth!’™

Hobart Stocking

SkyWaterEarth.com

hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Facebook: @SkyWaterEarthConnected

Twitter: @SkyWaterEarth

* It is also known as Hiŋháŋ Káǧa (‘owl-maker’ in Lakota)

Leave A Comment