The buffalo move like cloud shadows on the prairies around us. Heads down, they graze slowly. We are enveloped by a herd. The boys, Ian (10) and Teo (8), are transfixed with wonder.

The Hayden Valley of Yellowstone is bright and clear. White clouds punctuate a too blue sky. In late afternoon, everything is spring green. Today we have seen elk, pronghorn, black bear and grizzlies. I am glassing the tree line looking for wolves or bears, though it is the wrong time of day to see wolves.

Then I hear the car door opening. The boys jump out to gather Buffalo (Bison) hair. It’s not a great idea when calves are present among the heard. The buffalo may look docile, but can charge at up to 30 miles per hour.

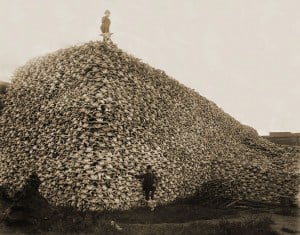

The buffalo is well known and immortalized in our literature and history. When the first immigrants landed in North America, there were 60 million on the continent ranging from northern Canada to Mexico, mostly across the great plains. They were hunted almost to extinction. By the late 1800’s, there were only 541 left. Commercial hunters slaughtered the majority of the herds.

This was part of a plan to starve First Americans into submission and onto reservations. It worked, and the great American prairie was ready to be turned into farmland. The government gave incentives for those who would homestead. The railroads provided transportation for both settlers, goods, and cattle back to the population centers of the east. The Native Americans were forced onto reservations. In our collective ignorance, this trend ran until the great dust bowl of the thirties.

There are now around 500,000 buffalo in North America. 15,000 are free ranging. Those in Yellowstone represent a genetically pure group. Most buffalo outside the park, have cattle genes, the product of a misguided attempt to make a “Cattlo.” Their offspring were mostly sterile, but a few of their genes survived.

Like our naïve and perhaps arrogant destruction of the buffalo, we are now faced with another issue. Catastrophic climate change. The great plains play a role in our climate and are a misunderstood and overlooked ecosystem. First they are a huge natural carbon sink. But continued farming and tilling are releasing carbon into the air faster than it is being sequestered. The buffalo and other grazing species could play a role in this process. Allan Savory explains how in this fascinating TED talk here.

Like our naïve and perhaps arrogant destruction of the buffalo, we are now faced with another issue. Catastrophic climate change. The great plains play a role in our climate and are a misunderstood and overlooked ecosystem. First they are a huge natural carbon sink. But continued farming and tilling are releasing carbon into the air faster than it is being sequestered. The buffalo and other grazing species could play a role in this process. Allan Savory explains how in this fascinating TED talk here.

The essence of his talk is that the soils of the great plains developed along with very large numbers of grazing animals. These grazing animals evolved with predators. (See my post, Running from Ghosts.) The predators kept the herds moving and kept them from overgrazing. Residual grass and dead matter changed the micro-climate next to the ground, increasing humidity and allowing more grasses to grow.

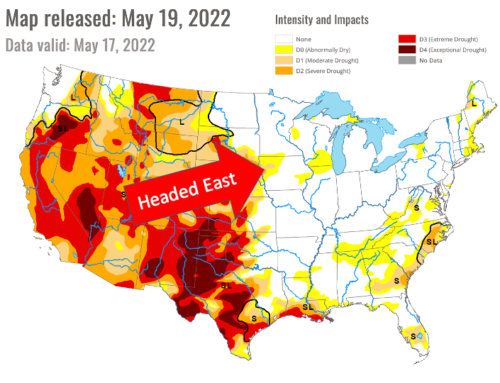

A few years ago I camped in the Buffalo Gap National Grasslands. I had a romantic notion of tall grasses blowing in the wind. What I found was hardpan. A cactus here and there, a cow pie, rock hard soil, and three feet away a blade of grass. Talking to a local rancher, he told me he raised 300 cattle on 6,000 acres of leased public lands. This process is repeated across the great plains. It takes inordinate amounts of water, land and carbon to raise cattle. This contributes to the desertification of the west. Desertification is now moving eastward at 15 miles per season. That doesn’t seem like much, but areas of western Nebraska and Kansas will soon become unproductive for raising crops, especially as the Ogallala aquifer begins to dry up. Within fifty years, a combination of heat, dry aquifers and desertification will leave western farmers with nothing to leave their children.

There are now some who propose “re-wilding” the great plains and letting the buffalo roam free. The idea is to take down the fences, reintroduce buffalo and wolves. It works in smaller areas, like Yellowstone (or read Buffalo for the Broken Heart by Dan O’Brien). It would result in more productivity than trying to raise corn to feed 300 cattle on 6,000 acres. But the cynic in me is doubtful. We will not give up our land. At least not until its worth nothing. Man above nature is our credo. People walked away from the dust bowl. We may not have this option.

The boys get back in the car. They hold up clumps of buffalo hair to their faces and pretend they have beards. They have faced danger and survived. What’s that smell I ask. Teo looks at his shoe. “Yuk, it’s buffalo poop,” he says. He exits the car to return it to the natural carbon cycle in the grass.

When he returns, I ask both boys about the concept of re-wilding. They are young enough to answer with a single word… cool.

We Are All Connected! Savor the Earth.

Hobie,

L. Hobart Stocking

SkyWaterEarth.com

hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Facebook: @SkyWaterEarthConnected

Twitter: @SkyWaterEarth

Leave A Comment