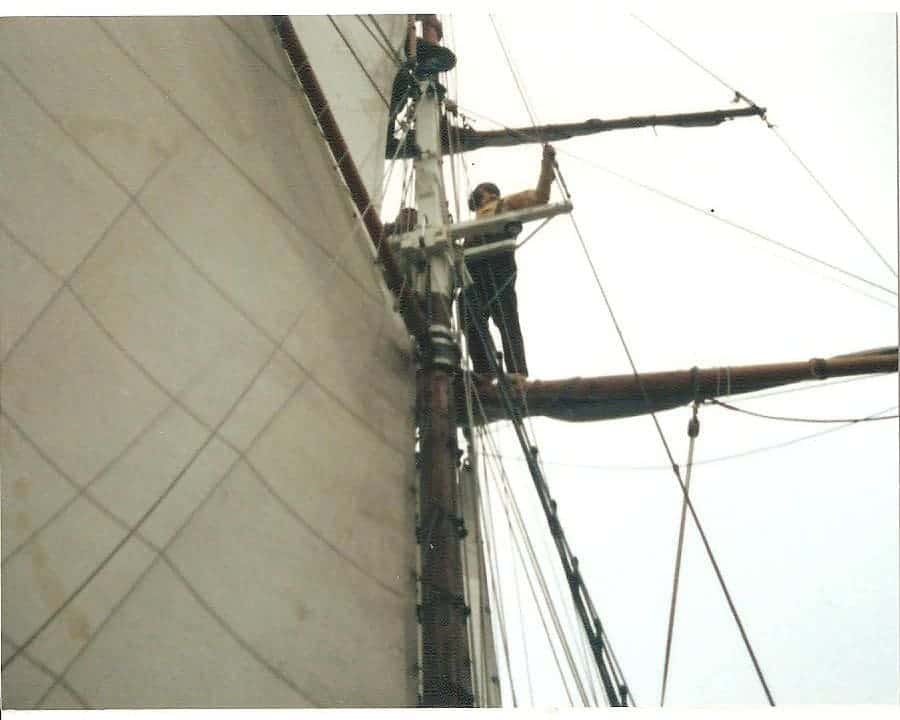

I climb the starboard ratlins and ease out onto the yard to unfurl the mains’l. My feet swing back and forth on a single footline. Working with my hands free, I am balanced on my stomach over the yard, making me wish I had a prehensile tail. The sail fills quickly. A high pressure front is moving through and we are in for a sleigh ride, a dead run to Isle Royale. I know it’s going to be tough when we try to bring the sail in later. The breeze is gentle now, but the waves are sure to build.

I climb higher into the rigging, up into the tops’l spreaders, and sit. I like it up here. The deck seems a hundred feet below. But it’s quiet with only the wind, cold blue water and anticipation ahead. From the deck one can see nine miles to the horizon on a clear day. The tops’l spreaders allow a view of the curvature of the earth. I imagine what it must have been like for early explorers sailing west into the Atlantic. The ship is small at fifty feet on the water and sixty-five feet overall. The water seems immense. It’s hard not to have reverence for nature in a small vessel.

The wind builds. By early afternoon we are in it. Twenty-five knots and a mounting fetch. The crew of eight is all sick, but the ship is fine. There’s an old saying that the ship will endure more than the crew. At the helm, I surf her down the backside of fifteen foot waves, the vessel exceeding her hull speed. While there is joy in being in the elements, I have no illusions. One broken piece of tackle, one careless grasp at a handrail and nature will show us how she doesn’t care. We are all just passing through this time and place.

In late afternoon, I don my oilskins on. At the wheel again, I turn to look at the lowering sun through a green wave breaking over the cockpit. For a second I am held by the light. Then the wave breaks white, filling the cockpit with cold water before draining out the scuppers.

At dusk, I site a few stars and put them in the rigging to maintain course. After another hour the the Washington Harbor light appears on the west end of Isle Royale. A welcome sight, we are dead on. I hand the helm over and go back aloft with my first mate to furl the main. In the dark, every step up the ratlins requires a force of will. The ship heaves in the swells. I imagine it’s a little like trying to thread a needle while sitting on a wild bull. But we succeed. Then the hook is dropped for the night in calm water. It’s been a good day.

The ship is the Sheila Yeates, a gaff-rigged ketch built in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia. From it, I will sail the next day to one of the world’s most interesting sounding place, The Amygdaloids, a series of small islands on the north side of the Isle Royale archipelago. This ship will carry me many places, though I don’t know it then.

I will sail the Atlantic, and watch a wright whale surface next to us and look me in the eye. I will watch phosphorescent streamers of startled sleeping fish scatter out from the bow like fireworks on St Georges bay. I will sail back into time in the fog of Gaspe to see only the masts of a dozen tall ships in the harbor. Godhavn, now Qeqertarsuaq, on the west Greenland coast will be a port of call.

There the ship will encounter icebergs calving off Lyngemark Glacier directly into Disko Bay. That was almost thirty years ago. When I spoke to another sailor who’d been there recently, I asked him if he had trouble with the ice. “What ice?” he replied. Locals say they use to dogsled to Ilulissat on sea ice in the bay until the mid-90s. But it completely disappeared within a decade. Melted and gone from global warming.

I’ve seen the world change with my own eyes in a single lifetime. The world is a precious place. We need to preserve it. Otherwise, what will we say to our children when there is no more ice?

We Are All Connected!

Hobie,

L. Hobart Stocking

SkyWaterEarth.com

hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Facebook: @SkyWaterEarthConnected

Twitter: @SkyWaterEarth

Leave A Comment