(This post first appeared in May of 2015 on Linkedin as part of a national project. Since it’s the new year and many of us take time to reflect, I thought I would offer it to my friends who are fighting for climate justice.)

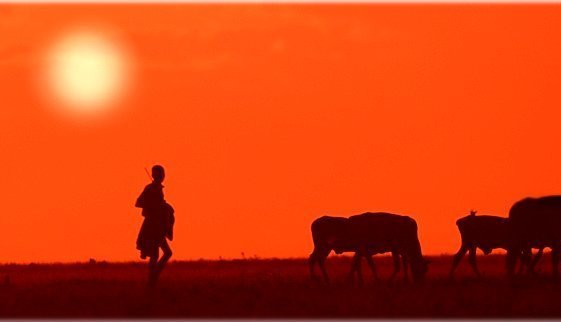

I was setting up camp with my wife near the Mara River just north of the Serengeti around my twenty-fifth birthday. The sun had just emerged below a reef of clouds on a race to horizon when I looked up. Silhouetted on a slight hill was a young Maasai boy herding cattle back to his boma, a thorn enclosure designed to keep lions out and people and cattle safe. It was then I heard the people in their village begin to sing.

I asked my wife to go down to the boma with me. For me, the sound of their singing was fascinating. But for my wife, a visit meant something else; biting flies, the awkwardness of an encounter with aliens, and the possibility of drinking milk and blood. While I had a few of the same reservations, I really wanted to go. She just said, “I’m not going, and I’d like you to stay here.” Going by myself didn’t seem like an option. I’ve always regretted not going that night.

What has this got to do with advice to my young self? Like a few of us, I was a product of a rigid childhood. I’d been trained to take the safe path, do the right thing, and eliminate risk. I spent the next twenty years creating businesses for a big bureaucratic company. I was successful, because I remembered having this regret. But I was still fearful, too cautious and too careful. Big companies inadvertently train their managers not to make mistakes. So I began to live my life resolved not to have regrets. I quit that company.

Many years later, when my daughter was fourteen, she said, “Dad, I’m going to South America next summer for three months.” There was no request for permission. I wrote it off to youthful fantasy. It made no sense for a fourteen-year-old to go alone and live in a small village in the mountains of South America. Her mother was vehemently against the idea, logically outlining the risks from disease and rape, to snakes and revolution. But in the end, my daughter used one argument to persuade us to let her go, an argument that I don’t hear enough of from business people, environmental groups, and corporations.

Risk has an internal and external component. To evaluate the external component, we can estimate project potentials, costs, investments, and probabilities. It was only years later I realized that returning after dark from the boma, that we would have been an easy meal for lions. Yet evaluating external risk is the easy part.

There is also an internal component of risk that is more important. It is our ability to assess and face our own fear. When we unnecessarily give into fear, we get regret, though we’re pretty good at rationalizing things later.

Facing internal fear and risk happens on a microscopic level every day for both business and environmental professionals. Should I speak up in a meeting against my director? What if the system I invest in doesn’t produce the results I’ve sold to my organization? What if this campaign isn’t successful? Should I hire this person…what if they’re not right? Often failing to identify these fears and take the safe route minimizes the apparent risk. It’s safe. It’s also a certain path to organizational death. Individuals and organizations needs to continually push the envelope against what is safe and what is a real risk. If you’re not doing this, then find another profession, or learn from the sales job my daughter did with me on why she should go alone to South America at the age of fourteen.

She used my own argument against me. She said, “Dad, you’ve always told me that the only things you regret are the things you haven’t done.” We let her go.

Fear is the enemy of opportunity, and we have too much of it today in our culture, our discourse, our politics, personally, and in business. Every day, I still have to ask myself, what are you afraid of? The young Maasai boy had only a spear and his courage. He’s my hero.

That’s the advice I would give my younger self: Make more mistakes, take more chances, carry a spear if you think it helps against the lions, and have no regrets.

We Are All Connected. Savor the Earth!

Hobie,

L. Hobart Stocking

SkyWaterEarth.com

hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Facebook: @SkyWaterEarthConnected

Twitter: @SkyWaterEarth

PS: More about the heart, this post is also about knowing when to stay and when to let go.

Leave A Comment