Cradled between three birch trees is where they will find me. I look at my rifle. A bolt action 30.06 manufactured by the Savage Arms Company of Connecticut. It has a Redfield 4x telescopic sight and is accurate to 200 yards. It can kill anything from prairie dogs to grizzly bears. Four years of skipping lunch and saving money to afford it.

Cradled between three birch trees is where they will find me. I look at my rifle. A bolt action 30.06 manufactured by the Savage Arms Company of Connecticut. It has a Redfield 4x telescopic sight and is accurate to 200 yards. It can kill anything from prairie dogs to grizzly bears. Four years of skipping lunch and saving money to afford it.

I am just fourteen. The idea of a deer hunt is exciting to me. I’ve never been hunting and only hear the stories of my older friends or the ones I read in magazines like Sports Afield or Outdoor Life. Together, with my father, my friend Bruce and his dad, the four of us head up to Itasca county for the opener.

I keep moving my right hand within my red glove, trying to keep my fingers warm. I read where hunters are not able to pull the trigger because of frozen fingers. I’m not supposed to, but I slip off the safety anyway. I can see my breath and wonder if the deer can also. There is no wind, and the woods is quiet and full of snow.

A raven lands in a tree about a hundred yards away and I imagine what it is like to be a raven. What is he doing here at this time of the morning? As I watch the bird, I decide that he is counting snowflakes in order to make sure they are falling in their proper places. My eyes are tired and the woods are peaceful, perhaps this is what it feels like before you freeze to death?

The raven jumps into the air with a single “caawww.” Something spooks him, and I strain to see movement in the dull gray light. There, on the hill, at a hundred yards, are two deer slowing walking at a diagonal to my stand. I watch them through the scope. It’s a buck and a doe. It seems strange that I can see them so closely through the scope. It’s as though I can touch them. The shot is an easy broadside at this distance, but for some reason, I hesitate. The longer I watch, the tougher the shot becomes, and I tell myself to wait. When they disappear over the crest of the hill, I decide to tell my father that it had been an impossible shot.

The sky is getting lighter and my feet now hurt badly. There are tears in my eyes from the cold. As I blink them clear, I am looking at yet another animal standing stock still fifty yards away. It is a large buck and he stands facing me, listening and turning his head from side to side. The picture in the scope looks like a cover of Sports Afield.

Yet, I still wait. Maybe… maybe I can get a better shot. I can see his breath… see him flare his nostrils, trying to pick up my scent.

The buck begins to step forward across a deadfall and I squeeze the trigger. The recoil from the rifle raises the muzzle, and I lose sight of the animal. I don’t hear the shot, but its echo comes ringing back to me from a thousand trees.

As I look again, the buck is laying on his side. I approach it slowly. I read where wounded deer sometimes jump up and gore hunters. I throw a stick at it. Then a stone. But the deer is dead.

I put down my rifle and look at the deer. One shot and now it is dead. There is no blood on his coat, and I take off my glove and brush my hand gently over him. His coat is coarse and cold to the touch. Not as I expect.

I count fourteen points on the rack, except that one is broken off. I sit down in the snow. I try to be excited, but all I can do is look at the deer. It is beautiful. It was.

Then I look up and out across the frozen slough in front of me. There, running at full speed toward my stand, is a very large black bear. He is two hundred yards away, but coming fast. I grab the rifle and check to see if there is a shell in the chamber, then run back past my stand. The bear seems panicked, as if someone shot at it. I can hear him crashing through the brush, moving directly toward my father’s stand.

The rifle is to my shoulder when the bear bursts into a clearing on top of a small hill, forty yards away. Suddenly, he stops, rises on his hind legs with paws dangling. His breath is steaming. As I look through the scope, I am presented with another magazine cover shot. It seems as though I am frozen in time, looking at the bear… the bear looking at me.

The only way I can describe what happens next is to say there is communication between the bear and me. It doesn’t speak to me. But it is something I can hear without sounds. I’m not sure what it is, but I lower the rifle. The bear stands for another second, and then drops to all fours and comes crashing on forward.

I lie down on the ground so as not to get shot by my father, and I say to myself, “Run bear, run this way…over here…this way…run!”

I can hear his chugging breath. There he is. Moving like a locomotive, ten yards away. Without slowing, he turns his massive head and looks at me. His eyes are dark. I don’t know if there is recognition. Yet, some bond exists between us in that second. My father’s thirty-thirty is still silent. When the woods become quiet again, I walk over to where the bear’s tracks cross the trail. I can still smell the bear. I take the safety off the rifle, then point it skyward and pull the trigger.

I walk carefully back up the trail toward the car. I think of the rifle in my hands and admire it, its satin wood stock, the blue black metaling of the barrel and receiver. It has a beauty all of its own, in its precision, its accuracy… in its deadly inertness. It is simply a rifle. It has no life in it. Then Bruce’s dad walks out of the woods near the car.

“Where are Bruce and my father?” I ask. He points to the car. The windows are frosted, but inside I see two figures asleep. I know my father is still hung over.

“I thought I heard shots…?” he says.

“Yes,” I say. “Yes, I shot a deer.”

“The second shot. It was late. You shoot at something else?” he asks.

“Yes, “I missed a bear,” I say.

When my father wakes up, he is proud of me. We drive through town with the deer on the roof of the car. Only half a dozen times.

When I get home, I put the rifle in its case in my closet and never take it out again. I sell it when I go to college to help pay for a different education.

-o-

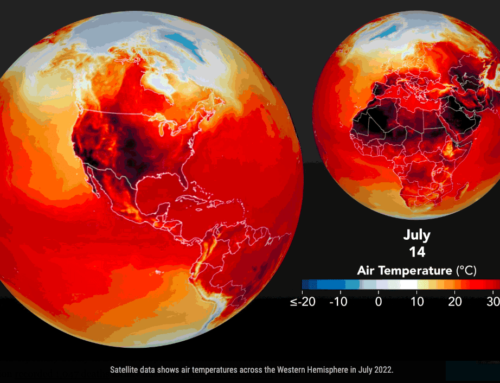

That was all fifty years ago. Now it’s warmer in November. We have very little snow anymore. I sometimes think of that bear. Mostly as I’ve grown older, and when I walk alone in the mountains or the woods. I think of the path I chose that day.

I’ve seen other bears over these years. There are fewer of them now. When I do see them, maybe it’s my imagination, but there is recognition in them. They walk close by. They are respectful.

The world is a smaller place now. It is not inexhaustible anymore. The moose are leaving Minnesota. The loons will soon be gone, and the pine woods will leave next. This doesn’t sound so bad. But what is coming will likely be worse.

The bears know this. The earth is trying to tell us this. We have no dominion over it. We are simply part of it. There are those who want to shoot grizzlies and wolves. Call them vermin. Those that want to use our rivers and air for sewers. They believe that man is above nature. Yet they are disconnected from nature. Perhaps their souls are ghosts. We can help to restore the earth. It’s the right thing to do. It’s the right path.

Recently, I am talking to an Anishinaabe man from Red Lake. We discuss his plans for solar power on the reservation. I ask him about wind energy, and he tells me that the risk is too high for the eagles. He says the eagles and the bears and the wolves are his ancestors. I think back to the bear. I know this.

We are all connected.

Hobie,

SkyWaterEarth.com

Hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Twitter: @skywaterearth

Facebook: @skywaterearthconnected

Leave A Comment