The following post is Part 2 of a 3 part series. The events occurred in August, September and October of 2016 and are being published now as all charges against me in the DAPL water protection recently have been dropped. These post are longer in length because I believe the whole story needs to come out. While the story is about my experiences, it is really about the bigger issue of climate change and fighting against a military and corporate based system that is poisoning the earth. It is also about indigenous rights and about a change in direction for America.

Heading West Again:

I am headed west again. Pushed by frustrations on getting the word out, and pulled by some force I do not quite understand. I am an adult who shouldn’t necessarily resort to impulses, but this one I am following. On the spur of the moment, I’ve cancelled my mail and thrown my gear in the car. My surface rationale is that the court decision on the Lakota lawsuit is coming down, and I fear that it’s going to go against the nations. They will need bodies to stand in the way.

I understand why I am concerned about the environment. I am not quite square with the why standing on the line is personally important to me. While the protectors are conducting a peaceful prayer event, I am willing to let fate determine whether I get arrested. More than this, perhaps I am really going back to find some piece of myself that I’ve lost. I learned a lot last time. Now I resolve to listen more, and separate what I am doing, from why I am doing it.

The Why:

I grew up as a feral child. I know I don’t look much like Tarzan, but I also lost my parents at a very young age.

I wasn’t raised by apes or wolves, but had the fortune to live in a place of lakes, rivers, swamps and forests. This was my jungle. It was my escape. As a kid I would get up before dawn, when the lake was like glass, dust floating on its surface, to go fishing. After sunrise I’d tromp around the woods watching for animals or finding bloodroot, trillium and marsh marigolds. I built forts of sumac and treehouses in a group of elms. I tamed a wild raccoon pup and named him Louis. Without adults, there was no text to this wild process, but I learned one thing. All things are connected.

I thought I wanted to be a forest ranger, but as I grew up, I studied science and graduated in Chemical Engineering, became a Marketer and Branding professional by vocation, and an entrepreneur by nature. Somewhere along the way, children and now grandchildren have happened.

While I was raising my family, I understood that the environment needed protection. In my day, the EPA was formed. Clean Water acts passed. Ozone holes started healing. I haven’t had my head in the sand, but I’ve been in denial. Thinking that some magical solution would appear for the problems we face or that someone else would take responsibility. The excuse was, someone else is working on this, right? I was busy.

I’ve even contributed to political campaigns, and environmental groups. Can’t I buy absolutions from climate tragedy through the Sierra Club? But the news is grim. It’s easy to lose hope and get cynical.

When I do, I try to remember again, that everything in nature and on earth is connected. Not just the physical processes, we humans are also connected. That the causes of poverty, discrimination, social justice and the environment are also connected. To make progress in one is to make progress in all. That if we are to change our path of environmental self destruction we must also change some of the worldview and values that underlay it; greed, fear and failed capitalism with unending consumption and rape of the earth.

Now my jungle is gone. The trillium and marsh marigolds are gone. The lake is filled with milfoil, zebra mussels, and water fleas. Last year the ice went off the lake a month sooner than it did when I was a kid. These are small changes compared to what is coming, and I am afraid.

When my five-year-old grandson, Teo, was visiting recently, we tried to find some jungle. He liked the patch we found. To keep him interested, I made up something called the Young Earthwalkers and I made up a “pledge” for him to take.

When my five-year-old grandson, Teo, was visiting recently, we tried to find some jungle. He liked the patch we found. To keep him interested, I made up something called the Young Earthwalkers and I made up a “pledge” for him to take.

He held up his hand and repeated these words. “As I walk the earth, I promise to preserve, defend and conserve our air, water, lands, and all living things that dwell in them, because we are all connected.”

When he finished, he looked at me and asked, “What do we do now Abba?” My heart stopped. My own grandson was challenging my passivity. Over the coming months, I thought about it. Finally figuring that if the pledge was good enough for him, then maybe it should be good enough for me. Otherwise Teo and my other grandchildren don’t stand a chance.

I am going back to Standing Rock for them in part. I am aware that the pipeline will emit 1.2 megatons of CO2 per week. We are cooking ourselves slowly. I don’t know if any small act I commit will make a difference, but I have no choice.

Gifts:

The way into Sacred Stone Spirit Camp passes the Cannon Ball Pit Stop. The last time I was leaving there, I spoke with a young Lakota girl of sixteen or seventeen. She said she wanted to go to an environmental college and study buffalo as a keystone species. I recommended a book to her on the subject. She wrote down the title, but when I got back I just decided to send her my copy. We didn’t introduce ourselves so I addressed the package to “Young Girl at Counter – Cannon Ball Pit Stop.” I had no reason to send a gift to someone I didn’t know. It just seemed like the right thing.

When I stopped and inquired about her, the man behind the counter picked up the package I’d sent and said, “We weren’t sure who ‘Young Girl’ was.” I described her, and he realized she was Jamie, daughter of the tribal leader. The book and the recipient would be united.

Connection:

The first person I met on this visit is Lisa, a Lakota from Rosebud. A naturalist and buffalo specialist, she travels around the country helping individuals and first nations improve their herds. We turn out to be analytical soul mates and talk for a couple of hours on subjects as big as buffalo, to issues of tribal mistrust, meth on the rez, and to the meaning of the gathering at Red Camp. I will connect her with Jamie.

The first person I met on this visit is Lisa, a Lakota from Rosebud. A naturalist and buffalo specialist, she travels around the country helping individuals and first nations improve their herds. We turn out to be analytical soul mates and talk for a couple of hours on subjects as big as buffalo, to issues of tribal mistrust, meth on the rez, and to the meaning of the gathering at Red Camp. I will connect her with Jamie.

We also talk about animals and the link to the spirit world. I tell Lisa that I like to hike at dusk and at night. The last three years, as I’ve walked down from Carlton peak on the North Shore of Lake Superior, I’ve felt a presence near me. As I’ve emerged on the road, the first year a wolf came out of the woods not forty yards away and then crossed the road in the same direction. The next year it was a gray fox. Last year it was a black bear. In turn, each stopped and looked at me, then continued onward. It was as if they were walking with me. Seeing these animals seems like a sign. Rationally, I don’t believe in signs. Only that I am comforted in some way and that there still seems to be wild in the world. Can I save the world if I can not savor it?

Lisa cautions me. Everyone, she says, is connected to another spirit creature. She is not sure if my animas is a winged animal or a four-legged animal. I wonder why I never hear of anyone who’s spirit creature is a salamander? However, she says there are “Wa-nu-gee” or spirits that roam the earth after dark which have never lived on earth before. They can give “unfair consequences” and can cause problems such as the palsy her brother suffered after going out alone at night. The practical and spiritual legend of her stories are a strange combination of new and old.

Later, I think about the Wa-nu-gee. I am never afraid in the woods at night. In coming to Standing Rock, I am searching for something. Part of this is the connection to the natural world that I’ve lost, but it’s also a connection to people. Have I lived on earth? Am I connected to a spirit animal, or am I part Wa-nu-gee myself?

Breathing:

I meet a Chinese man, raised in Jamaica and now a resident of Canada. He is a yogi in the first level of detachment. He has sold his home and possessions and is now traveling and living from his car. He seems open and reflective and I tell him about the Wa-nu-gee. I tell him about the way my brain works. Spinning faster than I like, how it sometimes separates me from myself and the world. He teaches me a breathing and meditation technique.

Later, I sit in the shade of a tree among the prairie grass and look out over the river. I realize one reason I am here is to savor the jungle I’ve lost. The prairie is beautiful.

Later, I sit in the shade of a tree among the prairie grass and look out over the river. I realize one reason I am here is to savor the jungle I’ve lost. The prairie is beautiful.

The wind is blowing gently across the sunny valley under a screaming blue sky. I watch white gulls catch insects in the sky, whirling and darting like swallows. An eagle circles counterclockwise from the right overhead and drifts down the horizon. The world passes and time slows down. I am breathing.

Action:

I run into Oyupota or Claw again. He invites me to go to the front line in the morning. I tell him that I don’t believe anything will happen in the morning. The judicial and administrative decisions were made late Friday. First the lawsuit by the tribe against the pipeline company, Embridge, was overturned. Then the Justice Department, Department of the Interior and the Department of the Army asked the Core of Engineers to ask the pipeline company to volunteer to suspend construction until a full review of the permitting process could be conducted. I know the way bureaucracies work and they don’t work on weekends. They will need Monday to decide what to do next and make their plans. Embridge is not prevented from construction. Things will happen on Tuesday, if they happen at all.

That evening I meet Oyupota a second time. He says he’s been called to provide security detail for tribal leader, LaDonna Bravebull Allard. There have been threats against her on social media. He says he will pick me up at 7:30 AM the next morning. Again, I am reluctant, but committed.

Training:

I walk along the river to Red Camp. It is now a small city, swollen to almost 5,000 people. Last time I was here there were 60 tribes. Now there are 220. Tipis dot the river valley. I see a horseman at full gallop careening along the river. Oyupota has made a suggestion to the elders of Standing Rock that they start a horsemanship school for the rez youth with the goal of competing in the next Olympics. Hope drives all of us forward I think.

I walk along the river to Red Camp. It is now a small city, swollen to almost 5,000 people. Last time I was here there were 60 tribes. Now there are 220. Tipis dot the river valley. I see a horseman at full gallop careening along the river. Oyupota has made a suggestion to the elders of Standing Rock that they start a horsemanship school for the rez youth with the goal of competing in the next Olympics. Hope drives all of us forward I think.

I go to school as well. After signing a bail information form and talking to legal council, I go to Non-Violent Direct Action training. It culminates with a role play. We are paired in twos, one person is an aggressor, the other a resistor. I am paired with a young woman from Palestine. There is no physical contact allowed, but as an “aggressor” we are instructed with a scenario of a sick child and the need to earn enough to help them. The resistors are keeping us from working, and therefore hurting our child. The woman facing me is 5’4”, slight and has incredible curly hair. I suspect she is an expert at this, having grown up in Palestine.

The exercise is to last one minute. When it starts, I put on my best angry white man demeanor and get six inches from her face and start yelling. She takes off her sunglasses, looks me in the eyes and simply smiles. Nothing I say affects her. She is totally silent and after an excruciating thirty or forty seconds, I simply melt.

When it comes her turn, she is fierce. She has a vocabulary most men would never use. I am intimidated by her power and maybe a little in awe. We give each other a hug afterward.

I discover she has a Doctorate from Harvard. That night we have dinner together and discuss social justice. She tells a story of arriving in Spain and being asked to go out to dinner with friends. She asks “What about the curfew?”, “What curfew?” they reply. She had lived every night of her life under Israeli restrictions.

We talk about her trip to Ferguson, MO and how we are both drawn to the disenfranchised. I observe that Sacred Stone Spirit camp is changing. There are a lot of non-natives that are coming. They are welcome, but seem to have the inclination to want to tell others how to run things. Her first words to the people she meets in Ferguson are, “What would you like me to do?”

Dishes and Dancing:

The thing I am asked to do is dishes. I have been at it for an hour when a young woman approaches and starts washing while I am rinsing. Her name is April. She is from San Francisco and headed to New Orleans. Very early in a conversation, she zings me.

The thing I am asked to do is dishes. I have been at it for an hour when a young woman approaches and starts washing while I am rinsing. Her name is April. She is from San Francisco and headed to New Orleans. Very early in a conversation, she zings me.

It’s a slightly teasing remark which I wish I could remember. My mind is blank. I stop rinsing dishes and stammer, “You caught me totally off-guard.” I laugh. “That was pretty good.”

“I’m trying to think of a witty repartee that will impress you, but I’m coming up with nothing. I don’t think I know you well enough to say what I’m thinking.”

“Go ahead,” she challenges.

“We’re there broken hearts involved in leaving San Francisco?”

“Only my own.”

I give her a sad look. “Tell me who it is and I will go slap some sense into them,” I say, and she laughs.

“I always wanted a big sister,” she says.

“I always wanted a little brother,” I banter. We are now going toe to toe and laughing.

“What brings you to New Orleans?”

“I’m a dancer.”

I pause just long enough, “Exotic?” I ask. People are now turning around to see what all the laughter is about.

“Occasionally,” she smiles.

Then I ask her, “Will you teach me how to dance?”

Without skipping a beat, she says, “Exotically?”

I confess to her that I’ve never danced. She says, “It’s easy. You just let your body move to music.” We have a moment.

When we are done with the dishes, I ask her how old she is. “Let me guess, you are twenty….”

Before I can finish, her shoulders drop. “I’m thirty-five.” She seems sad. She is the same age as one of my daughters. What would I say to them?

“April, I don’t know what you’re looking for, but you know you are beautiful person. You’ll find it.”

Later that afternoon, I look for her to say goodbye. I can’t find her, and never see her again.

That night I can’t sleep. I am supposed to go with Oyupota in the morning to the front line. I am spinning around the prospect of being arrested. I doze off around midnight and awake at 1:30 AM. There is singing coming from Red Camp and the drums are still beating. As I lie there, they seem to be coming up under me from the deep in the earth. I crawl out of my tent. The grass is cool and wet on my bare feet. The moon is bright, and the fires have died. The people around me are now sleeping in their tents. And I begin to dance.

The coyotes are laughing from the hills now. But my feet keep rhythm. I realize I am connected. I am ready for tomorrow.

Ready or Not:

I am up before the sunrise. It is cold and gray. I place everything except my driver’s license in my car and climb a small hill to wait for the sun and Oyupota. The camp is still asleep. The sun rises as a red streak under a reef of clouds. Seven thirty comes and there is no Oyupota. I tell myself that time is an elastic thing in this country. At 8:00 am I walk up to the security gate for the camp and ask Mekan to see if he can radio Oyupota. There is no answer. At 8:30 am I accept that he is not coming. Things seem calm, I am thinking I may leave the next morning.

Gifts and Leaving:

Leaving Sacred Stone Spirit camp early, I decide to drive up Highway 1806 past Red Camp and up through the state roadblock. It’s shorter and more convenient. Locals complain that Red Camp and the blockade are disrupting their lives. It seems unlikely that a 30 second stop at the blockade can be much of an inconvenience. They are most likely afraid, but afraid for the wrong reasons. The Lakota are trying to protect the land and water. For everyone.

The principle they operate from is asking how any decision affects the next seven generations. That seems to make sense to me. But how are we to cope when our horizon is the next paycheck, or a job for the next year, or the next election? They are guided by the phrase, Mni Wiconi, or ‘Water is Life’. They know that the decisions and actions they take today will affect all of us for generations.

Data from USDA finds that the US corn crop decreases 0.7% for every day over 84°F. Because each year is now getting warmer, over the next 60 years, yield across the US is expected to decrease by 33%, not including droughts. For the state of Iowa alone, this means a $2 billion-dollar crop loss over the next ten years. But since it happens slowly, the next barrel of oil seems more important. It may be, but there are better alternatives. This is what the Lakota are trying to tell us.

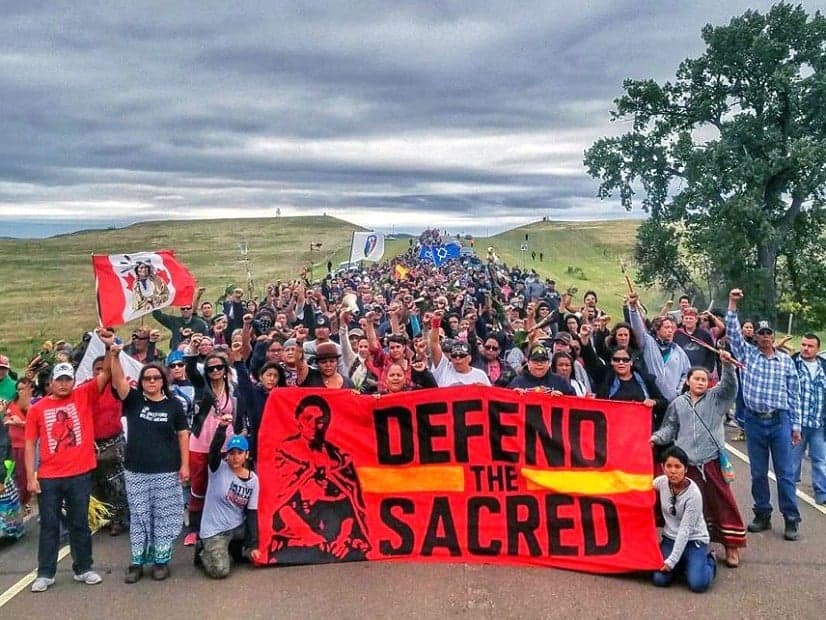

I pass Red Camp and wonder if the people here are not ghost dancing. The ghost dance was performed by natives in the late 1880s after they had been forced onto reservations with the idea it would unite the living with spirits of the dead to make the white colonialists leave, and bring peace and prosperity, and unity to the the tribes. As an act of prayer, defiance and desperation, it was of course outlawed by the BIA and US Government. It was also thought by the Lakota to protect them from bullets through spiritual connection. I pray that doesn’t happen.

I pass the first protest site, a fence draped with flags and see it has grown. In another mile, I see another site. It looks like the front has moved. I stop to see if Oyupota is there and to say goodbye. I meet a young Cheyenne man. His name is White Horse. He has steady and reflective eyes. I tell him I am returning to St Paul for a rally of solidarity that night. After parting, he goes to his car and takes something out then approaches me again.

Please take this back to St Paul. He holds out a sage bundle with two hands palms up. I thank him and tell him I have nothing to give him now, but will return. He says it costs nothing. It is a gift from mother earth. So be it.

I place the bundle carefully on the seat of my car. It smells like the prairie. Soon I am passed by a Federal Police vehicle. I look at the sage and wonder if the patrolmen, guards at the roadblock or the national police know the difference between sage and gange? I have a mission now. Bringing this gift back to St Paul. So I stop and place it in the trunk of my car.

When I return to St Paul, I learn that the State of North Dakota arrived later in the day with dozens of troopers to arrest 20 protectors. They are in full black riot police regalia. Helmets, boots and shields. The resistance is peaceful and prayerful. I believe the police are actually afraid. But something must be done, of course, about those ‘Indians.’ Ghost shirts can not save them.

When I return to St Paul, I learn that the State of North Dakota arrived later in the day with dozens of troopers to arrest 20 protectors. They are in full black riot police regalia. Helmets, boots and shields. The resistance is peaceful and prayerful. I believe the police are actually afraid. But something must be done, of course, about those ‘Indians.’ Ghost shirts can not save them.

I am worried about the short term chances of turning public opinion on the Dakota Access Pipeline. Most people in North Dakota have made their minds up. Oil is a boon. It’s good for the economy. But the issues presented by the Lakota here are bigger. Something special is happening here at Standing Rock. Whether we are smart enough to notice is another thing. Maybe it’s time we listen to the wisdom of the First Nations? It’s a gift.

Savor the Earth! We are all connected. Mni Wiconi.

Hobie,

L. Hobart Stocking

SkyWaterEarth.com

hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Facebook: @SkyWaterEarthConnected

Twitter: @SkyWaterEarth

Leave A Comment