Dusk lights the long corridor ahead of me through jack pine and colored maple. I am on my way to a small lake to watch the sun set. In electric mode, the only sound is the soft crunch of the car’s tires on gravel. The air is still with the edge of coming winter.

One hundred and fifty yards ahead of me I spot something on a bare branch to the left. I wonder how I am able to see things in nature so easily. I grew up in the woods and somehow trained myself in animal vision. Embedded in my brain are fractal pattern templates of the north woods. When something breaks this pattern, my brain compares it to a template in memory and signals the difference. This is the way predators, like wolves and hawks, see the world. It’s not a conscious process.

Closer, the template reveals a gray owl, a big beautiful bird on the southern edge of its range. Just before I come abreast, the bird gracefully launches itself off it’s perch and heads down the road with me. Its wings beat slowly and silently. I glance at my speedometer and we are matched at 23 miles per hour. It seems I can almost reach out and touch the tips of its broad wings. Owls have fourteen vertebrae in their necks and don’t move their eyes, but rather turn their heads to see. I am not a vole or a mouse, but the bird turns toward me and looks. What do its piercing bright yellow eyes tell its brain? Then I am casually dismissed as the owl turns into a glade. We have been companions for thirty seconds. This image now forms a template. (You can listen to a gray owl here.)

At the lake, I watch a loon feed in an orange swath of light against a blackening forest shore. Loons fly at seventy miles per hour and migrate to the Gulf of Mexico or Nova Scotia. The shape of migrating bird’s wings is an evolutionary adaptation. The loon’s are narrower and longer than the owl’s. (Listen to the call of the loon here.)

Owl Eggs

These two birds, on different branches of their ancestral tree, share the same geography while existing in separate ecological niches. Later, I look them up and see pictures of their eggs. Gray owls lay one to three eggs in nests deserted by other raptors.

Loon Eggs

Loons also lay an average of two large eggs in protected marshes nests, though I have seen nesting pairs with at least five chicks. The owl’s eggs are round like ping pong balls, and the loon’s are elongated, and I wonder why their eggs are so differently shaped?

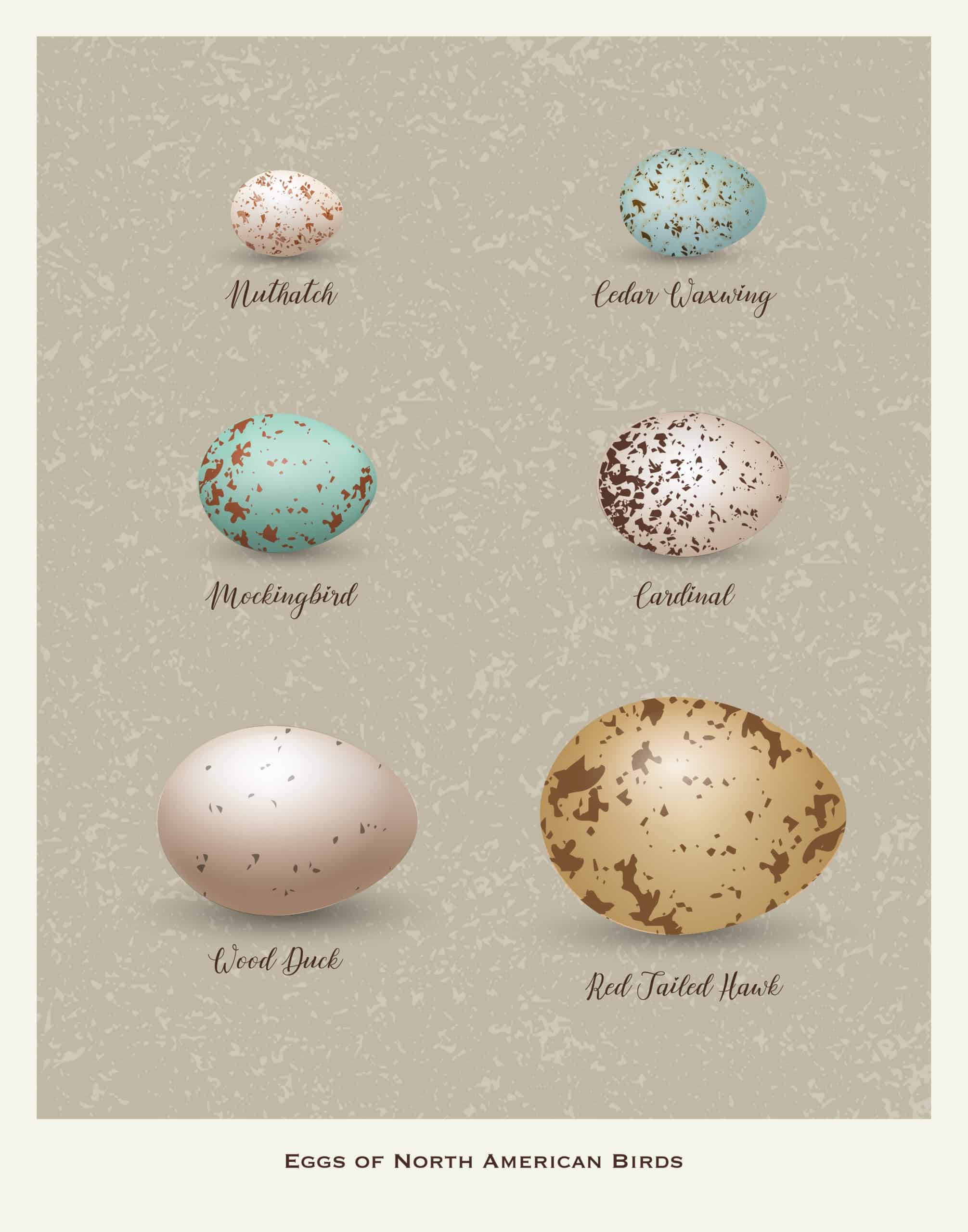

Eggs are quite beautiful, and it turns out that there are a lot of theories about why they have different shapes. Some think it’s due to the number of eggs laid, or the shape of the nest. Some eggs are long and pointy. No eggs are square, which would keep them from rolling out of the nest. But I suppose that they would be difficult to turn over when incubating.

An evolutionary biologist at Princeton, Mary Stoddard, studied this question. She wrote computer programs to analyze the photos of over 50,000 eggs. She studied whether some shapes had stronger shells to escape breaking, or were perhaps easier to break for hatchlings. Her results were a big goose egg.

Then she created a bird family tree, putting hawks on one branch, terns on another, loons and divers on yet another. She began to notice that birds on the same branch had similar shaped eggs. Those like the tern and the loon that migrated long distances were long and oval. Birds like the gray owl that liked to vacation at home were round.

It turns out that the shape of the egg developed to accommodate the aerodynamic shape of the bird and the bird’s pelvis which evolved for flight and migration. Imagine trying to fly 5000 miles with and abdomen full of round eggs. I wonder about their shape had the earth a different tilt on its axis on its trip around the sun, or if the air were denser or lighter than it is.

The air seems infinite to those of us who are gravity bound. But the air that surrounds the earth is thinner than the skin of an apple compared to the apple. Only four to five miles thin. It protects us from the cold black depths of space to keep us at just the correct temperature for water and life. Its density is such that it helps evolve the wings of migrating birds and shapes their eggs.

We are a product of this environment, not separate from it. As such, we need to protect and restore our air, water, and land, and not exploit it. We lack the understanding to claim mastery. So when we protect the water, the land and this thin shell of air, we protect these birds, but more importantly, we protect ourselves.

We are all connected. Savor the earth.

Hobie,

L. Hobart Stocking

SkyWaterEarth.com

hobart@skywaterearth.com

651-357-0110

Facebook: @SkyWaterEarthConnected

Twitter: @SkyWaterEarth

Leave A Comment